Week 1 Discussion Notes

Table of Contents

Symbols

Definition

- "for all" or "for any" or "for every"

- "there exists"

- "is in" or "is an element of"

- "implies"

- "subset"

- "proper subset"

These will be your best friends in this class, so get used to using them all the time.

Remark.

A weird thing is that a lot of mathematicians use "" and "" to mean the same thing, even though everyone uses "" and "" mean different things.

Set Theory

Common Sets

Here are some very common sets that we'll be using throughout the class:

- "empty set"

- "natural numbers" (in our textbook, natural numbers start at , but that might not be the case in other books)

- "integers"

- "even integers"

- "rational numbers"

- "real numbers"

We will be covering the construction of these sets (especially and ) in great detail a little later in the class, but these are the sets that you "know" already.

Remark.

is a subset of every set. The idea goes like this: if were not a subset of , then there exists such that . But has no elements, so . This is an example of a vacuous truth.

Set Operations

Definition

Let be sets. Then

- The union of and is .

- The intersection of and is .

- The complement of is .

Let's understand these one-by-one:

- Taking the union of and just means dumping everything in and everything in into one bigger set.

- The intersection of and means everything that's in both sets.

- The complement of is everything that's outside of (i.e., everything that's not an element of ).

Now that we have some basic set operations, it's natural to ask what happens when we mix them together:

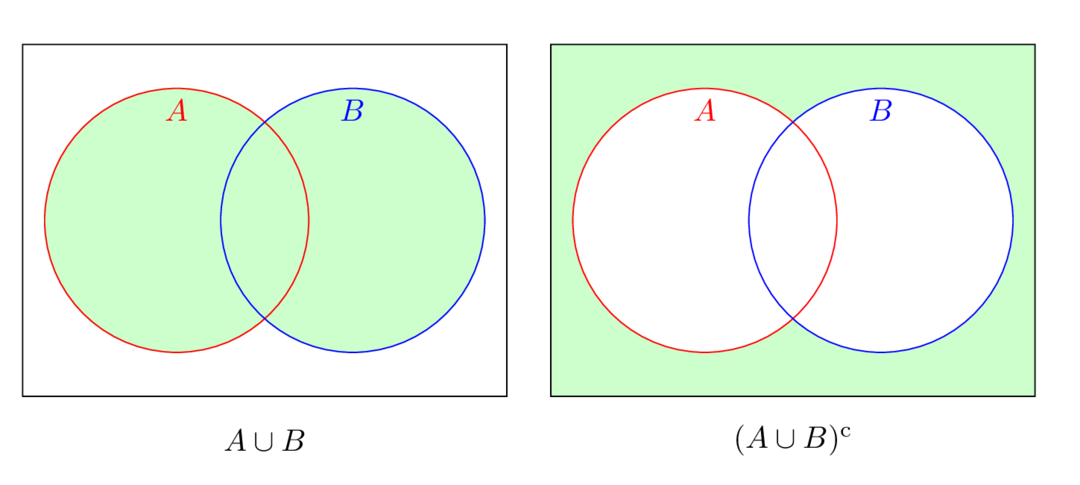

Proposition (De Morgan's laws)

Let be sets. Then

Proof.

(i): If , then is in at least one of or . The negation of "at least one" is "none," so if and only if and , which means

Here's the picture:

(ii): The idea is the same: if , then is in both and . The negation of "both" is "at most one," so if and only if or . This means

Exercise 1.

Draw a picture for .

Definition

Let be sets. Then

- The power set of is .

- The cartesian product of and is .

Like before, here's a less mathy way of looking at these sets:

- The power set of is the set of subsets of , so it's a set of sets.

- The cartesian product of and just means you pick one element of and one element of and put them in a pair.

Example 1.

If , then

Example 2.

If , then

Notice that and that is both a subset of and an element of .

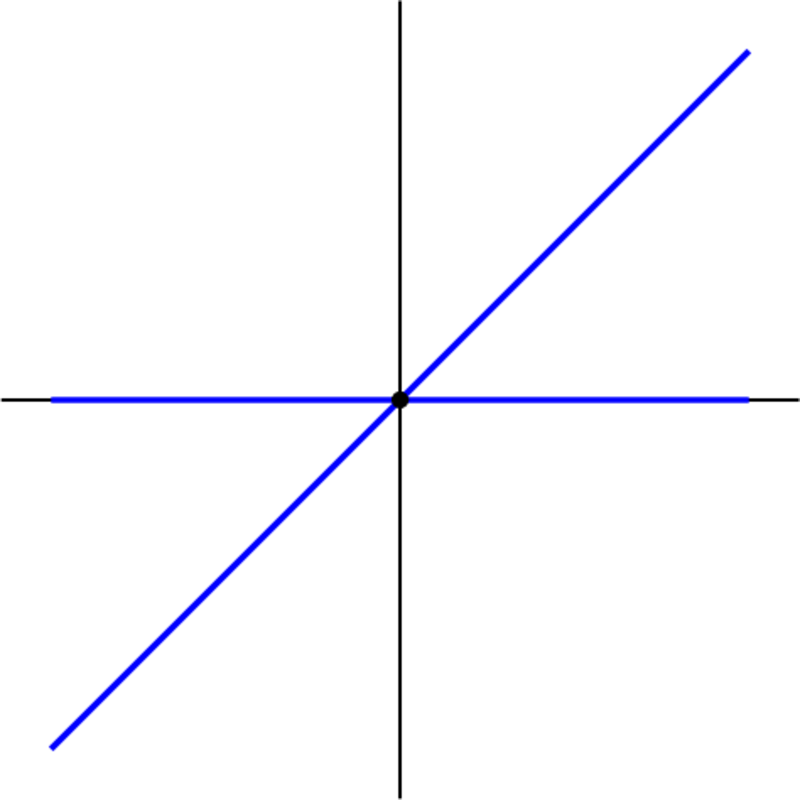

Example 3.

. This is the 2D plane, and we also write it as .

Counterexamples

It's good to know a lot of counterexamples to prevent you from writing down things that are wrong. A lot of times, something is "intuitively true," but turns out to be false. For example, when I took Calc AB in high school, I wrote something like this:

Since is continuous, it is differentiable somewhere.

I now know how wrong I was, but as a beginner, this made sense to me since it was true for every example I could think of. The issue was that I wasn't exposed to enough counterexamples. This statement is false because there are functions which are continuous everywhere, but differentiable nowhere.

Examples

Example 4.

True or false: If is continuous at , then it's continuous on an interval containing .

Solution.

This one is false. For example,

The graph looks something like this:

At any point you're going to "jump" between the lines and , so you're discontinuous if . However, if you follow both lines to , they both converge to , which is why is continuous at .

Example 5.

True or false: If is continuous and converges to the function, then converges to also.

Solution.

This is false. See this Desmos graph.

To see why converges to , you can slide to be any number in . You'll see that if is large enough, then the spike won't include . But no matter what is, my example always has , so the integrals can't converge to .

Example 6.

True or false: If is continuous, then the image of is still an interval. (An interval is anything of the form , or .)

Solution.

This is true because of the intermediate value theorem (it's a bit technical to explain in detail, though, but we'll revisit this in the future). This is also related to something called connectedness, which is covered in MATH 131B.

The main takeaway from these examples is that there is bad intuition and good intuition. Knowing counterexamples helps you get rid of the bad intuition, which helps you avoid making mistakes.