Week 1 Discussion Notes

Table of Contents

Exponentials and Logarithms

Basic Properties

Definition

Let b>0 and b=1.

- bx is called an exponential.

- logbx is called a logarithm.

The reason why we're avoiding b=1 is because 1x=1 for any x, which isn't interesting to us. Same thing for b=0. Lastly, we don't want to deal with negative values of b because we could end up with something like (−1)1/2 which is an imaginary number, which is not covered in this class.

These functions have the following properties:

domain(bx)range(bx)b0bx+y(bx)y=(−∞,∞)=(0,∞)=1=bxby=bxydomain(logbx)range(logbx)logb1logb(xy)logb(xy)=(0,∞)=(−∞,∞)=0=logbx+logby=ylogbx

These properties should look pretty similar to each other to you. For example, the domain and range of the two functions are swapped, and the fourth line is "swapping addition and multiplication." This is because bx and logbx are inverses:

blogbx=xlogb(bx)=xif x>0,for all x.

Proposition

Let a,b>0 both be different from 1. Then

logbx=logablogax.

Proof.

The proof of this formula is good practice for using the properties of these functions. First, let k=logbx. Then because bx and logbx are inverses,

bk=blogbx=x.

Then if we apply logax on both sides, we get

loga(bk)⟹klogab⟹k=logablogax.=logax=logax

□

This is how I personally remember the formula: first, I remember very roughly what it looks like:

logbx=logaloga

From here, I see that b is below x in the left-hand side, so it stays below in the end:

logbx=logablogax.

Differentiation

When b=e (Euler's number), a lot of really nice things happen. For example,

dxdex=ex

e is so important that logex has its own symbol: lnx, which satisfies

dxdlnx=x1.

Using the properties of exponentials and logarithms, we can use the facts above to find the derivative of bx for general values of b. Notice that b=elnb, so

bx=(elnb)x=exlnb.

Then by the chain rule,

dxdbx=dxdexlnb=exlnb(dxdxlnb)=bxlnb.

Similarly, if we use the change-of-base formula,

dxdlogbx=dxdlnblnx=lnb1(dxdlnx)=xlnb1.

Integration

Since integration and differentiation are (almost) inverses, the fact that dxdex=ex tells us that

∫exdx=ex+C.

As before, we can use this fact to calculate the integral of any bx:

∫bxdx=∫exlnbdx=∫lnbeudu=lnbeu+C=lnbexlnb+C=lnbbx+C.(u=xlnb⟹du=lnbdx)

Surprisingly, we can't integrate lnx with what we've learned yet. We'll learn later how to do it, but for now, just know that

∫lnxdx=xlnx−x+C.

Logarithmic Differentiation

Which is harder to differentiate, exsinx or ex+sinx? You (hopefully) said that the first one is harder, and that's because derivatives are easier with sums than with products.

The property that logb(xy)=logbx+logby is very useful for us because it turns the product into a sum, and we can use this (with the chain rule) to make some derivatives easier to compute.

Example 1.

Let f(x)=exsinx. Use logarithmic differentiation to calculate f′(x).

Solution.

Notice that

lnf(x)=ln(exsinx)=lnex+ln(sinx)=x+ln(sinx).

Then by the chain rule, taking derivatives on both sides gives

f(x)f′(x)=1+sinxcosx.

Multiplying both sides by f(x)=exsinx then gives

f′(x)=exsinx+exsinx⋅sinxcosx=exsinx+excosx.

Examples

Example 2.

Calculate dxdlog2x.

Solution.

You could write down the derivative from the formulas, or if you don't remember it, you can use the change-of-base formula:

dxdlog2x=dxdln2lnx=xln21.

Example 3.

Find the equation of the tangent line to y=log2(1+4x−1) at x=4.

Solution.

To specify a line uniquely, you need two pieces of information: a point through the line and its slope. For a tangent line at x=4, the line must pass through (4,f(4)) with slope f′(4). So, we need to calculate f(4) and f′(4):

f(4)=log2(1+44)=log2(1+1)=log22=1.

For the derivative, we get

f′(x)⟹f′(4)=(1+4x−1)ln21⋅dxd(1+4x−1)=(1+4x−1)ln21(−x24)=(1+44)ln21(−424)=−8ln21.

So the tangent line passes through (4,1) and has slope −8ln21, so if we use the point-slope formula, we get

y−1=−8ln21(x−4).

Example 4.

Sketch the graph of f(x)=x−ln(x2+1).

Solution.

Curve sketching is pretty hard to explain over text compared to during the live discussions. I'll explain my approach and give some resources to help you sketch it.

Before sketching, I like to calculate two sets of things:

- The zeroes of f′(x) (these are the critical points of f)

- The zeroes of f′′(x) (these are the potential inflection points of f)

For (1), you get

f′(x)=1−x2+11⋅dxd(x2+1)=x2+1x2+1−x2+12x=x2+1(x−1)2.

So the only zero of f′ is x=1. For (2),

f′′(x)=(x2+1)2(dxd(x−1)2)(x2+1)−(x−1)2dxd(x2+1)=(x2+1)22(x−1)(x2+1)−2x(x−1)2=(x2+1)22(x−1)[(x2+1)−x(x−1)]=(x2+1)22(x−1)(x2+1−x2+x)=(x2+1)22(x−1)(x+1)

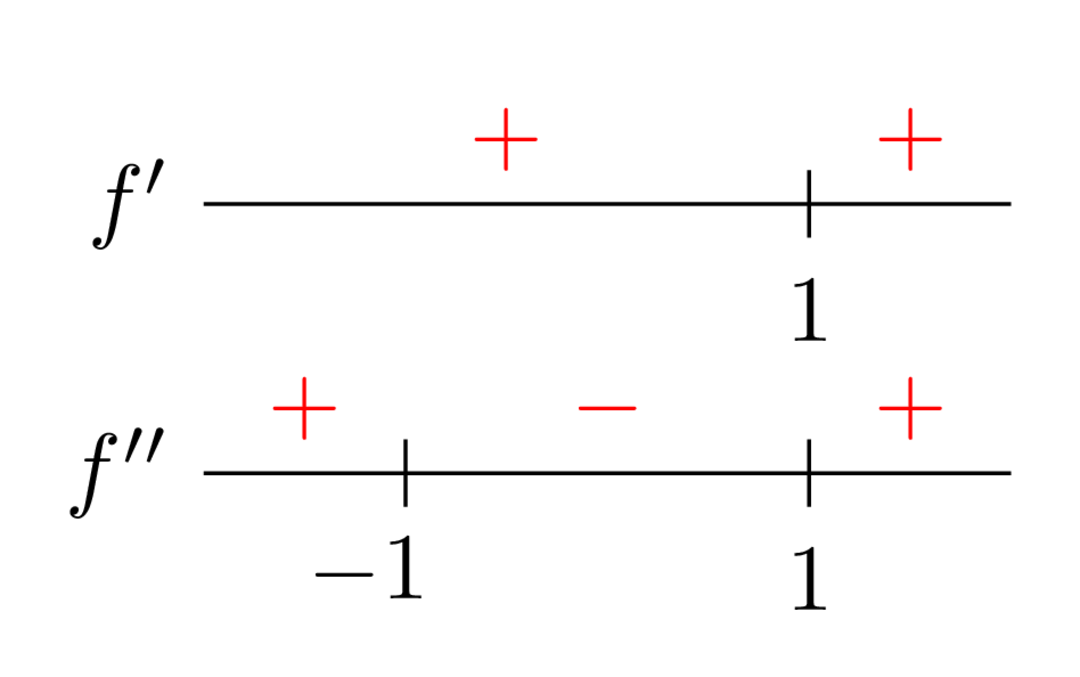

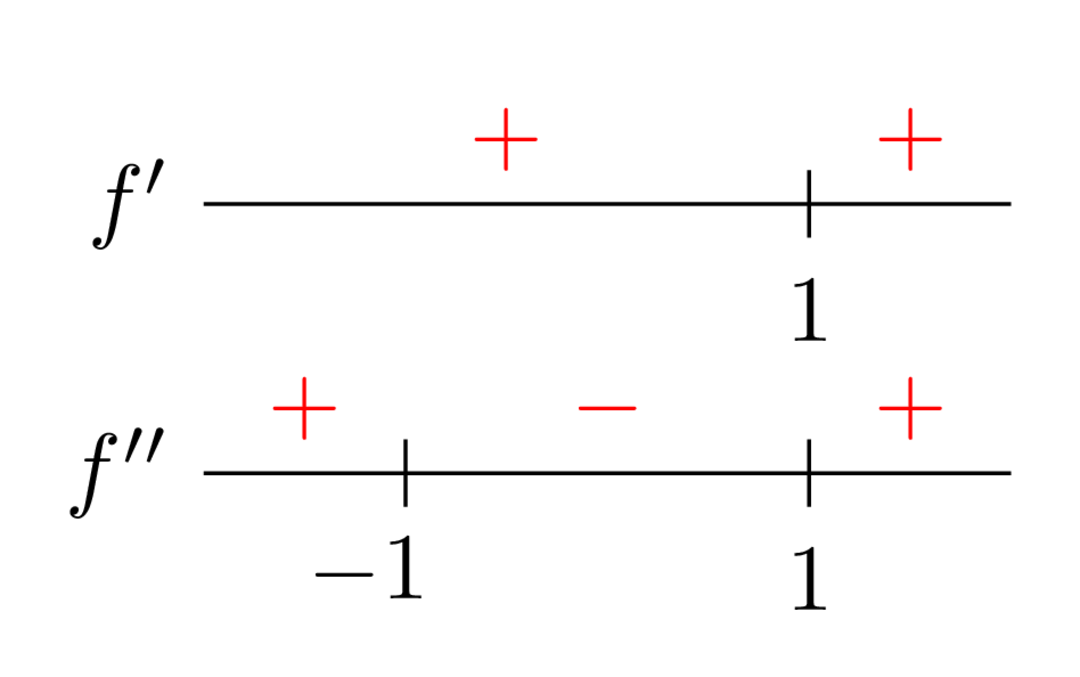

which gives x=−1,1 as the potential inflection points. From here, you can figure out the signs of f′ and f′′ everywhere:

The sign of f′ tells you whether f is increasing or decreasing, and the sign of f′′ tells you whether you're concave up or concave down. You can look at these notes to see how the signs translate to the rough shape of f. You can also use Desmos to graph f to check your answer.

Example 5.

Calculate ∫xlnxdx.

Solution.

If u=lnx, then du=x1dx, so the integral becomes

∫xlnxdx=∫udu=ln∣u∣+C=ln∣lnx∣+C.

Example 6.

Calculate ∫x(lnx)ln(lnx)dx.

Solution.

Similar to the previous one, we can let

u=ln(lnx)⟹du=xlnx1dx.

Then

∫(xlnx)ln(lnx)dx=∫udu=ln∣u∣+C=ln∣ln(lnx)∣+C.